Vaccine Q&A, 5th Edition

Georgia COVID-19 Updates, 19Mar2021

Before we get going, I just want to remind my readers that I am not a medical doctor and cannot provide medical advice. Always consult your physician for addressing your unique medical needs. This newsletter is instead more of a general understanding of the science and an attempt to provide clarity on some of the pressing questions that people have about the vaccine. Overall, the vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective, nearly eliminating the risk of severe COVID-19 infection that results in hospitalization and/or death. But I think it’s fair to ask questions and desire answers. My ultimate goal is to answer your questions to the best extent possible with data so that you feel empowered and informed about your decision, either way. If you’d like to read the previous editions of Vaccine Q&A, they are linked below.

1st edition topics: the pace of vaccine development in 2020, phases of eligibility, how do the vaccines work?

2nd edition topics: why are two doses needed for the RNA vaccines? What are the time intervals between doses? Can I mix and match vaccine manufacturers for dose 2? Storage conditions and why there are “throw away” doses potentially at the end of the day. RNA vaccine ingredients. Should I get the vaccine if I’ve already had COVID-19?*** What if I’m exposed or sick between doses? Reactogenicity and can I use an NSAID to manage those symptoms? Safety tracking for COVID-19 vaccines. When might we expect vaccines for kids?

3rd edition topics: Johnson and Johnson clinical trial data. EUA process for the vaccines. Pregnancy and fertility. What can you do after vaccination?

4th edition topics: the path back to “normal.” Herd immunity. Long term effects of the vaccines. Johnson and Johnson vaccine ingredients. Is there antifreeze in the vaccine? Should I get vaccinated, even if members of my family aren’t currently eligible? Should I wait and let others get vaccinated first? How long does immunity last?*** Will COVID-19 become endemic?

***We’re going to revisit these topics today in light of new information.

Why do I need a vaccine if I’ve already had COVID-19?

We got a big study out of Denmark this week that followed people that were tested during two surges of disease, in the spring and in the winter. They identified the people who tested positive during the first surge and then checked to see how many of them tested positive again during the second surge. Of 11,068 patients who tested positive in the first surge and were tested again in the second surge, 72 of them tested positive during the second surge. Against the control group, they were able to calculate that previous infection was 80% protective against subsequent infection for the entire study group. For those 65+, protection against reinfection was reduced to 47%. So this means that 1 in 5 people could get infected again. Among seniors, this means that about half of them could get infected again. They were also able to follow about 2.5 million people over the long term and among those who were protected against reinfection, that protection didn’t seem to wane after the 7 month mark. They didn’t investigate individuals for the presence of antibodies, symptoms, etc.

So what does this mean? It means that for a lot of people, their protection from natural infection might be longer lasting than we previously thought (>7 months compared to the 90 days we’ve been thinking). However, without antibody testing, we can’t tell by looking at a person whether they’re one of the unlucky 20%. And people might be walking around thinking they’re immune when they really aren’t. Compare that to a vaccine like Pfizer or Moderna, where symptomatic infection is reduced 95%, and we can see that the vaccine still has a lot of value for those who have been previously infected (95% protection compared to 80%). This is not a perfect comparison because the Denmark study didn’t investigate symptomatic versus asymptomatic infections. But this study makes it even more important to vaccinate those 65+ who have already had COVID-19. The immune system starts to decline at the 65 year mark and it’s a function of normal human aging. It’s possible that these folks aren’t mounting as robust of an immune response as their younger counterparts. So if you’re 65+ and you’ve already had COVID-19, it’s really important that you get a COVID-19 vaccine. If you’re younger than 65 and have already had COVID-19, it’s a good idea to go ahead and get vaccinated anyway, because a one in five chance of reinfection is actually rather high.

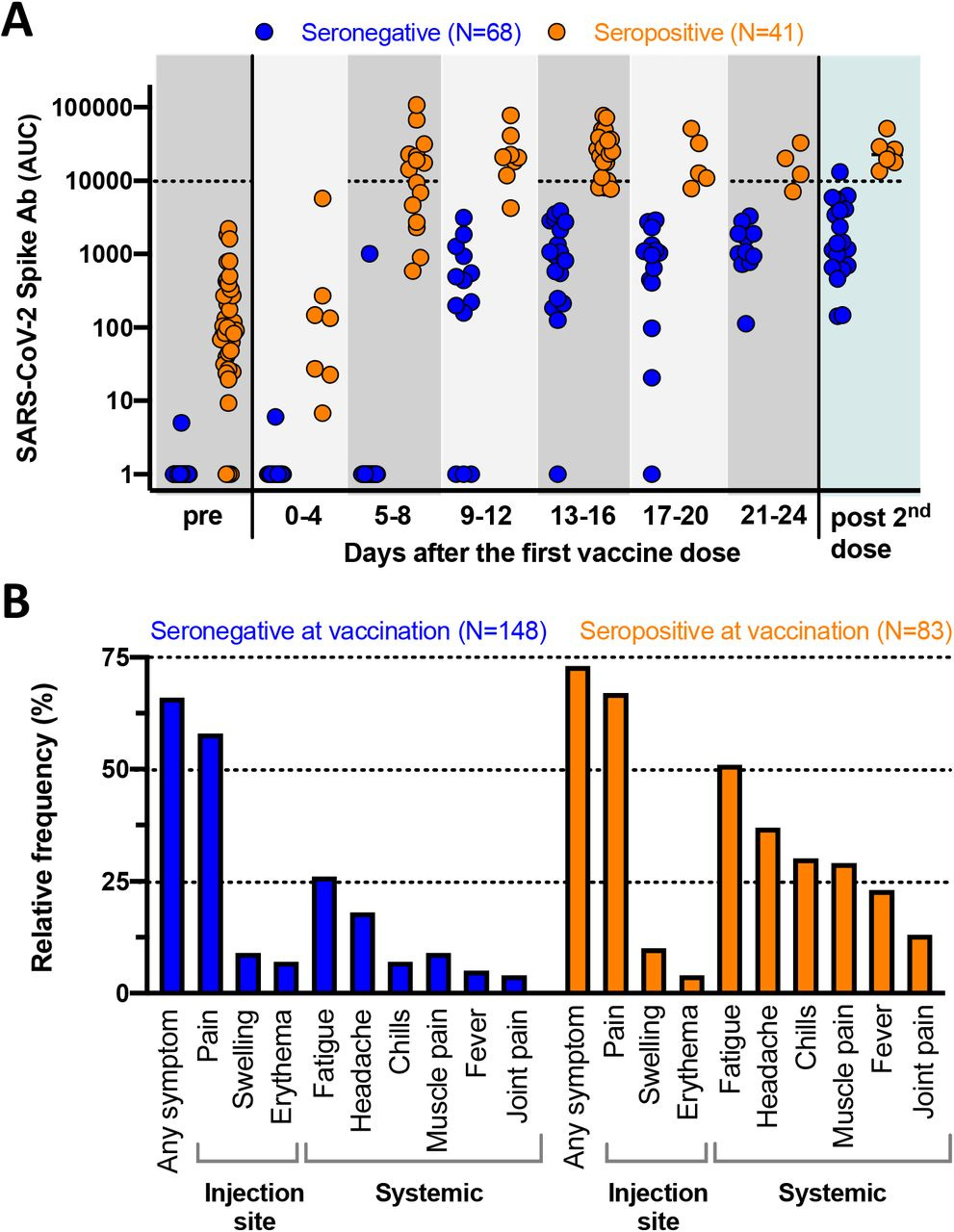

We can look at antibody data among those who were vaccinated after previous infection. As a caution, you should know that this study has not yet undergone peer-review by the scientific community. So consider this a heads up or early evidence but possibly subject to change. Let’s look at the “A” part of the figure first. This graph is measuring antibody concentration among people with pre-existing immunity to COVID-19 (orange) versus those without that immunity (blue). On the left, we can compare the two groups before any vaccine is given and you can see the clear difference between them. After vaccination (looks like it was Moderna based on the time course) they monitored the two groups and sampled their blood for antibodies at the time intervals along the x-axis of the graph below. It took 9-12 days to see an improvement among those in the blue group (not previously infected), but by day 21-24, all of them were producing antibodies. For those in the orange group (previously infected), they saw antibody concentration increase at the 5-8 day mark and their antibodies exceeded those produced in the blue group by the 9-12 day mark. However, look at how spread out the people were in their antibody concentrations in the orange group in the first two time points after vaccination and even prior to vaccination. There are winners and losers in this graph for the orange group - those who produce a LOT of antibodies after infection and those that produce less. Consider the pre-vaccine data. The people below the 10 mark on the y-axis of that orange cluster of dots are producing less antibody than the blue group does after vaccination. So are these people actually immune? Maybe not, and probably not as much as someone who is vaccinated, regardless of their past infection history. There was no real change when they looked at immunity after the second dose (days elapsed is not defined here). Note, we don’t get any demographic details on the people tested here including age. Perhaps these missing pieces will be corrected during peer review.

Next, let’s look at panel “B.” This looks at reactogenicity symptoms among those with and without pre-existing immunity (orange and blue groups, respectively). These are the symptoms we expect to see during an immune response. They are not adverse events. Almost across the board, we can see that these symptoms were more common (this graph does not measure severity, only frequency) among the people with pre-existing immunity. The most common symptoms were pain at the injection site and fatigue.

The authors argue that the vaccine functions like a booster for those who were previously infected. And there really wasn’t a lot of benefit in giving them the second dose, however we don’t know how long they followed these individuals. It’s possible there was an improvement with time. However, since there doesn’t seem to be a big benefit at this juncture to give the 2nd dose to previously infected people and their reactogenic symptoms tend to be more common, the authors argued that perhaps only one dose was necessary for those with previous infection. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices considered this paper and whether to recommend a single dose for those previously infected. They ultimately decided no. The reason being that we would need to do antibody testing on every person who was previously infected prior to vaccination to confirm pre-existing immunity. That’s not feasible given testing limitations and the scale of the vaccination effort. In addition, this is a relatively small sample size (83 previously infected people) to make such a conclusion that would affect millions of people. However, they plan to seek out additional data for this and perhaps a different decision will be made in the future.

Taking the Denmark study and the antibody study together, it very much makes sense to get vaccinated after COVID-19 infection. But there may be different priorities for vaccinating previously infected people based on age. The studies show us that not everyone’s immune response to natural infection is equal. There are people who have robust antibody production and those who produce relatively few antibodies. Again, we can’t tell which of those people you are without an antibody test. Part of the reasoning to give vaccines to those with previous COVID-19 infection is to give everyone the same baseline of protection. But based on what we went over today in the Denmark study, it is more important that people 65+ get the vaccine, regardless of their past infection history. I think it would be a good idea for all age groups too, but if younger adults who were previously infected want to wait and let those with no pre-existing immunity get vaccinated first, that’s probably okay.

What if I have Long Haul COVID-19? Should I be vaccinated?

This is a good time to remind the people who like to type in all caps that 99.99% of people survive that (a) that percentage sounds impressive but isn’t correct and (b) survival and death are not the only outcomes of COVID-19 disease. Most people survive polio too. But survival with paralysis is a pretty significant outcome as well and the primary reason why we vaccinate. There is a subset of people who survive mild to severe COVID-19 with long term health impacts that can include the symptoms shown in the chart below. This comes from a pre-print study (so not yet peer-reviewed) that looked at how vaccination affected symptoms in long haul COVID-19 patients in the UK. They selected patients who still had at least one long haul COVID-19 symptom 8 months after their infection and interviewed them 1 month after their vaccination. They compared this population to a matched cohort of long haul COVID-19 patients who did not receive the vaccine. Pay close attention to how the blue and yellow sections (improved and worsening symptoms, respectively) changed between the groups.

In the unvaccinated cohort (left side), 9 symptoms improved and 10 got worse by the 8 month mark. For those who were vaccinated, 13 symptoms got better and five symptoms got worse for some of the patients. This was a small study and it is important to gather more data about this. But early indications are that the vaccine can offer some improvement of long haul COVID-19 symptoms and a decrease in worsening symptoms. The authors concluded that these patients should be considered for vaccination just like anyone else in the general population.

Autoimmune conditions and history of allergies

Autoimmunity is a phenomenon where your immune system mistakes a self-antigen (something native to your body that is supposed to be there) for something foreign and attacks it. Sometimes the self-antigen looks really close to the antigen of a previous infection, sometimes it’s something where we never really know what triggered the errant immune response. A lot of the times these conditions can’t really be cured but can be managed with medications that dampen the immune response. That helps to alleviate the symptoms of the autoimmune condition, but it can leave patients more susceptible to infection. They can also impact the person’s ability to respond to a vaccine. When we talk about herd immunity and the need to vaccinate so many of us that those who can’t be vaccinated are also protected, some people with autoimmune conditions and immunosuppressing medications are among the people we want to protect with our immunity.

Because there is such a wide spectrum of autoimmune conditions and medications to treat them, it is best to speak to your physician about your unique medical history and concerns (if any) about the vaccine. Both the CDC and the Georgia Department of Public Health do consider these people to be both eligible AND prioritized for vaccination, because the risk of severe outcomes from natural COVID-19 infection is so high.

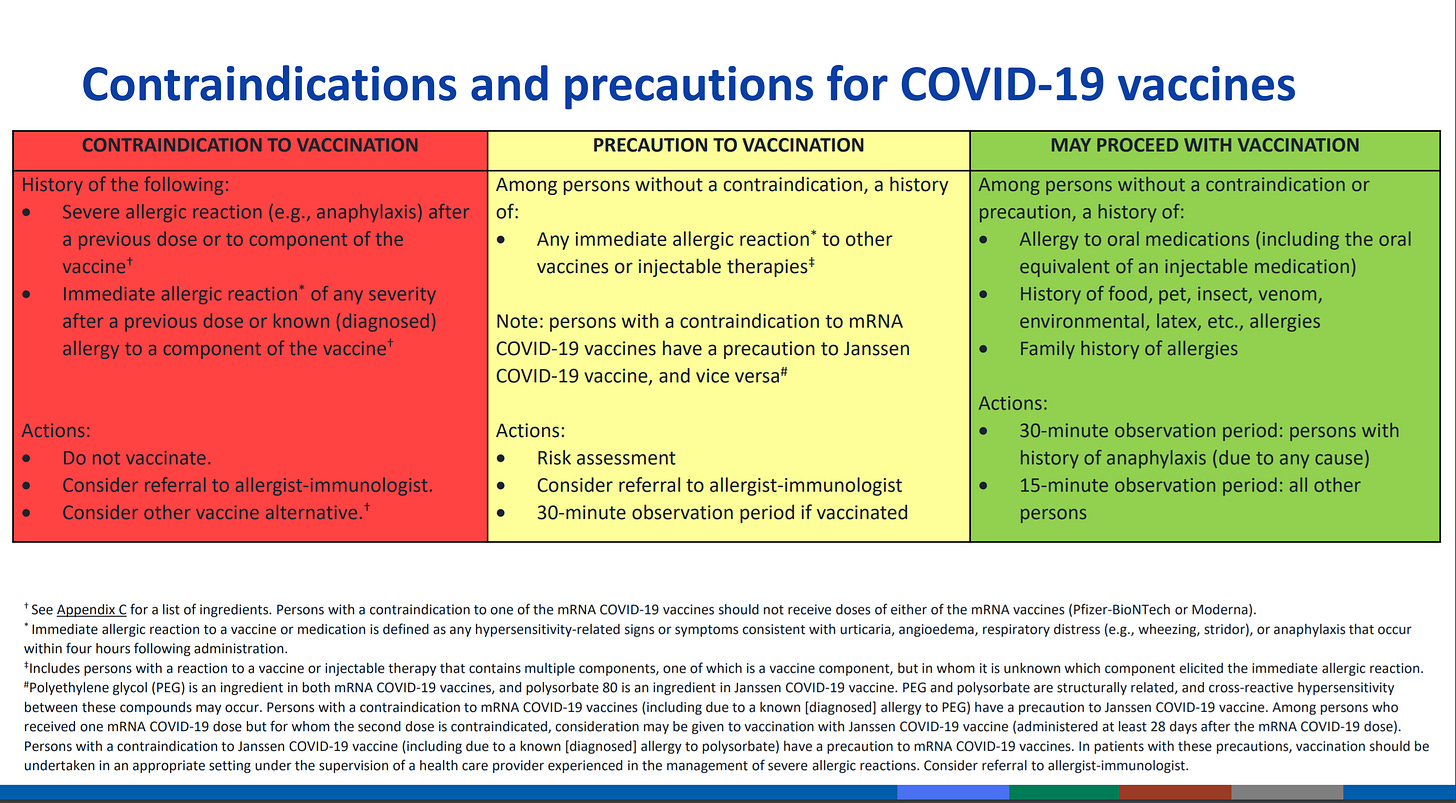

Next, let’s talk about past history of allergy. At the last Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meeting they offered a table of guidance for people with certain allergies. Contraindications are situations when a person should not be vaccinated.

For people with a severe allergic reaction to the 1st dose of the vaccine or to components of the vaccine, it’s recommended that they not be vaccinated (red box). For those with history of allergic reaction to other vaccines and injection medications, they may want to get their vaccine at an allergist/immunologist’s office where they can receive better monitoring than they might at other vaccine clinics and mass vaccination sites (yellow box). And these individuals should be monitored for 30 minutes after vaccination, rather than the 15 minutes recommended for the general population. They note that if someone has a contraindication to the mRNA vaccines, they can consider getting the Janssen (Johnson and Johnson DNA vaccine) or vice versa. The green box indicates that people with past history of allergy to oral medications, food, insects, venom, latex, etc, or a family history of allergies CAN get the vaccine. But if these folks have any history of anaphylaxis they should stick around for 30 minutes following vaccination. Of course, if you have additional questions or concerns, please raise them with your physician or with the provider at your vaccine appointment.

Disinformation surrounding vaccines

I’m getting a lot of emails that start with “I saw this video on YouTube…” So I want to remind people of a couple things. Google and YouTube are not accredited universities or medical schools. They are websites where anyone can share anything they want, with little to no fact checking. They are not great places for medical advice. Science and medicine share their findings in academic and medical journals following a process of peer-review (scientific fact checking). As a result, getting quality information out to the public is sometimes slow. However, conspiracy theories are fast. And one of the fastest ways to share them with the world is to put them on YouTube. YouTube is good for a few things: demonstrations on how to fix things around the house, how to make great food, planning travel, etc. But it is not a good place to get medical information.

So if you see or hear something that causes alarm on YouTube, I want you to pause for a moment and think…have I seen this same topic discussed elsewhere at a trusted source of information with the same conclusion? Science has a self-correcting aspect that is based on confirming the findings of others or disproving them, in order to form a broader consensus that can be the basis for future hypotheses. So if you’re not seeing the same topic being discussed by doctors and scientists in scientific publications and webinars among well-respected experts, etc, with the same conclusions, then it likely isn’t verified or true. Was I scared about this before watching the YouTube video? The reality is that videos on YouTube that make sensational claims are the ones most likely to be liked, shared or commented. And all of that can be monetized for the person who posted the video. So it is in the poster’s financial interest to make the claims most likely to cause fear. The bigger the claim, the bigger the evidence is needed to make it true and virtually none of these videos are bringing the data with them to prove what they’re saying. They play into the fear and anxiety that surrounds the “unknown” aspect of this evolving pandemic. On the same vein, I want you to read my writing with a similarly skeptical lens. Check the linked references, see if what I’m saying makes sense when you read them.

All this to say that I think it is perfectly reasonable to have questions about the vaccines and I want you to get answers, to the extent that science is able to provide them. But I want to make sure you have a moment of self-reflection to gauge whether these are your genuine fears and worries or something that someone else told you to worry about. And what does a person have to gain by inciting that fear and anxiety?

Another thing I am getting a lot of is people saying they are “terrified” of the side effects associated with the vaccines. I think people are getting whipped up into a hysteria over symptoms that are similar to a hangover. Do you have this kind of panic before going to a party with friends? Again, I think this is a situation where sensationalized claims (media, YouTube, social media, etc) require us to take a moment and pause to think critically. These symptoms are expected signs of an immune response. If feeling tired, having a headache, maybe a fever and some muscle aches are terrifying, perhaps you’ve never been sick a day in your life. Or have never had a child in daycare or school bring infections home to you. The symptoms (reactogenicity) following vaccination are expected and minor. They can be managed with over the counter pain medications (prefer tylenol over NSAIDs early on) and a day on the couch watching TV. Drink lots of water and you’ll be fine. If you have symptoms above and beyond the expected, that’s different of course. But a day or two’s discomfort from these expected symptoms is no comparison to an ICU stay or 8 months of long haul COVID-19 symptoms (remember the study above, 8 MONTHS!). This is a situation where it’s helpful to know what to expect, but we shouldn’t get worked up over expected symptoms. If that were the case, no woman would ever go through childbirth and none of us would be here. I think we can recognize that there are things in life that are worth doing, despite temporary discomfort.

Miscellaneous

I am running out of space here, but I want to briefly mention and refer you to stories that are making news right now.

Blood clots and the AstraZeneca vaccine. Blood clots can happen for a variety of reasons in the general population, and the number of blood clot events observed with the AZ vaccine is less than or equal to what we would expect in an unvaccinated group of people of the same size. So we can’t really link the clots to the vaccine at this point. Birth control pills actually have a greater risk of blood clots than this. None of this is to say that blood clots aren’t serious - they certainly are and need to be treated. But we cannot conclude that the vaccines were the cause. They are likely an artifact of coincidental timing and not causation.

A report of the first baby in the US born with COVID-19 antibodies after her mother (a healthcare worker) was vaccinated for COVID-19. This is another benefit to consider when weighing whether to get vaccinated while pregnant. In this case, the mother was 36 weeks pregnant (close to term) at the time of her first dose of the Moderna vaccine. The baby was born at 39 weeks, before mom’s second dose.

General outlook

Usually this is where I would talk about what’s going on in Georgia. But there’s something we need to pay attention to that has statewide and national implications today.

Georgia has really struggled with its vaccine rollout and built up a stockpile of 1.47 MILLION doses while being consistently ranked near the bottom of the rankings for vaccinating its population. But things are looking up. In fact, yesterday the state set a new record with 109,875 vaccine doses administered in a single day. The graph below is presented with permission from Grant Blankenship of Georgia Public Broadcasting. It uses CDC data curated by the Associated Press to measure doses shipped to Georgia and doses administered per day, represented by a 7-day moving average. We can see for about the last month, Georgia has been taking in more doses than it has been giving out which explains why the state has a stockpile of doses. HOWEVER, that gap is narrowing and Georgia’s 7-day average of doses administered has more than doubled since the start of March. I don’t think any of us demand or expect perfection, but we do expect improvement. And this is a HUGE improvement. I think a lot of this success is due to the GEMA mass vaccination sites and expanded eligibility, but I know there are so many vaccinators out there working hard on this. It must be a cool thing to go home and reflect on what you did that day, saving lives that might otherwise have been lost.

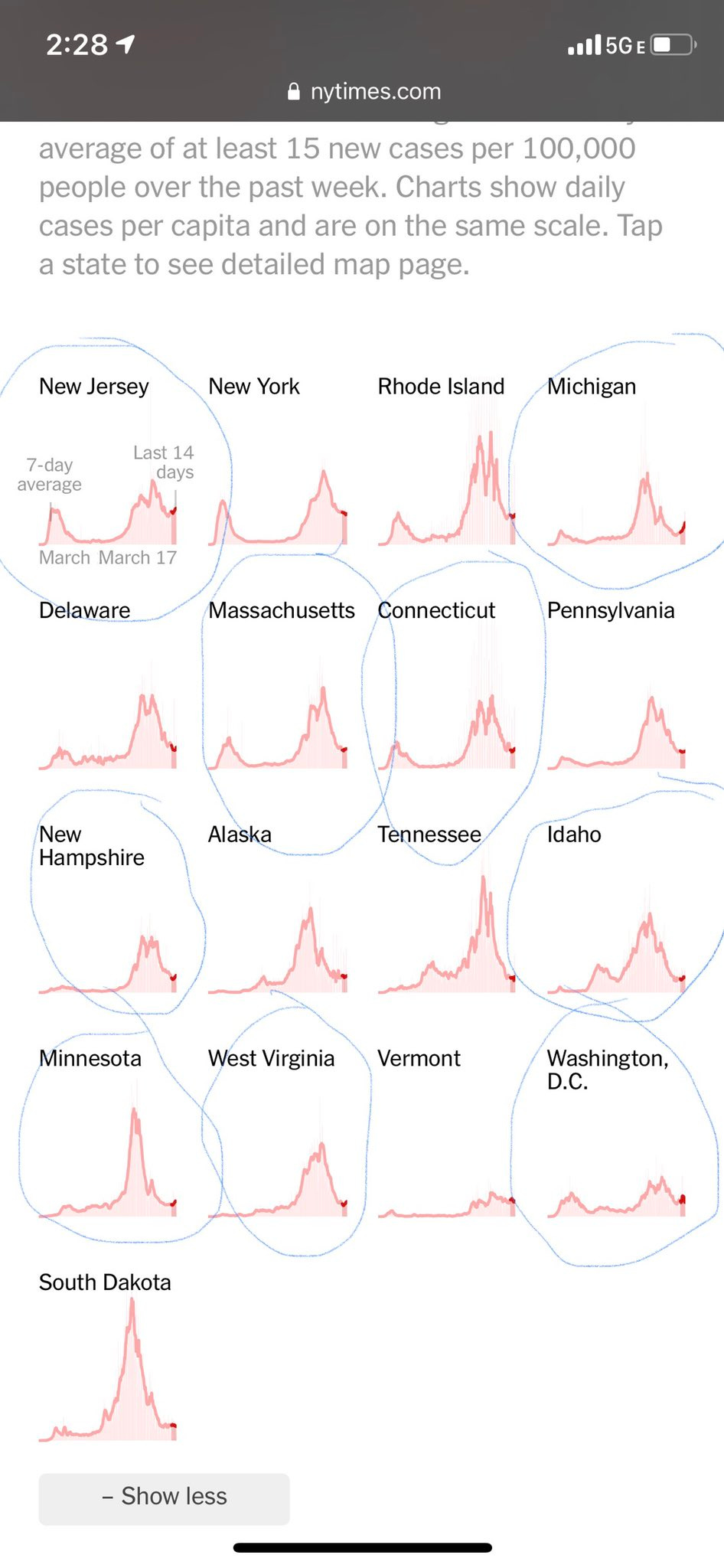

But even as the vaccination effort is getting better in Georgia and throughout the country, we are seeing signs that COVID-19 is not done with us. The race to vaccinate people as quickly as possible is competing against increases in disease in some states, people relaxing their disease mitigation strategies, and more transmissible variants. I shared the image below from the New York Times on Twitter yesterday highlighting that we have at least 9 states that are showing increases in their case rate over the past few weeks. These are not one or two day swings in the data, but sustained increases. That means these trends are likely real and not an artifact of delayed reporting.

What’s also interesting is that some of these states are those who lead the current effort in vaccinations. What this tells me is that even though they are leading in vaccinating their population, we still aren’t close enough to herd immunity yet to prevent further surges. We have not yet vaccinated enough people to give up on mask wear and social distancing. It would be a shame to lose more people when have a vaccine because we are impatient for a return to normal. Please, please give the vaccine effort a few more weeks to vaccinate people at the very least. We’ve waited a year. We can wait a few more weeks. Georgia has seen its case rate increase 13% in the past four days. I think we need more time to confirm that this is a trend and not just the result of a couple bigger than usual reporting days. But we should take any increase like this as a good reminder to keep adhering to public health guidance and get vaccinated at the earliest opportunity.

Georgia COVID-19 Updates is a free newsletter that depends on reader support. If you wish to subscribe please click the link below. There are free and paid options available.

My Ph.D. is in Medical Microbiology and Immunology. I've worked at places like Creighton University, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and Mercer University School of Medicine. All thoughts are my professional opinion and should not be considered medical advice.