Vaccine Updates

There have been some developments since I did the Vaccine Q&A series that I want to talk about today.

Safety in Pregnancy

A big question that comes up again and again is the safety of the vaccine when it comes to fertility and pregnancy. I’ve discussed this before and there really isn’t any evidence that the vaccines impact the ability to get pregnant, stay pregnant, doesn’t impact pregnancy outcomes nor development of the offspring after birth. Those who wish to disinform just have to raise the specter of possibility to incite fear, but offer no evidence to support their claim. They capitalize on an emotional topic. And it’s easier to prove a “yes” than a “no.” In this case, we’re having to prove a “no” which means continuing to search for needles in a haystack that may not, actually, exist in the first place.

I’ve discussed the v-safe program before also. This is a text message based app that anyone who receives a COVID-19 vaccine in the US can use to report their symptoms following vaccination. It also tracks special populations, including those who report that they are pregnant. Some of these data we already had from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meetings, but now they’re in peer-reviewed, published form, meaning that they’ve been vetted and scrutinized.

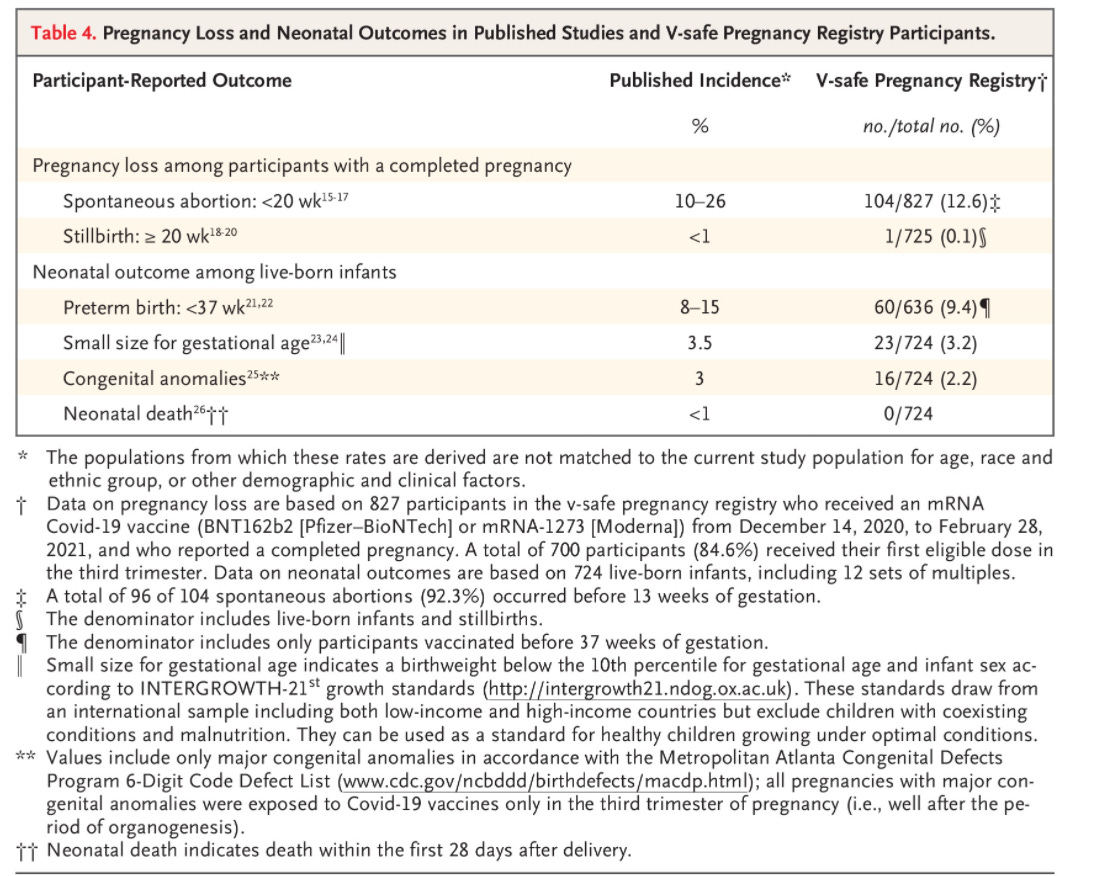

As of February 28, 2021, there had been 35,691 pregnant persons identified through v-safe who had received a COVID-19 vaccination. Those who were pregnant were more likely to report pain at the injection site and fatigue as symptoms than non-pregnant vaccine recipients. But they reported other symptoms less frequently than non-pregnant recipients. The CDC researchers then enrolled a subset of these pregnant people (n = 3958) in a study to follow pregnancy outcomes. Of this subset, there were 827 completed pregnancies during the study period. The researchers compared various pregnancy outcomes among those who were vaccinated compared to the typical frequency of those outcomes in the general population (published incidence column in the table below). So pay attention to the published incidence column and the percent of that outcome among the completed pregnancies among vaccinated people on the right (in parentheses). For all of the metrics they examined, the frequency of pregnancy loss due to spontaneous abortion (also known as miscarriage) or stillbirth was similar to normal trends. The frequency of complications such as pre-term birth, low birth weight and birth defects was the the same or less than what is observed in the general population.

I think we should continue to follow up on this and gather more data, but so far these findings are very reassuring.

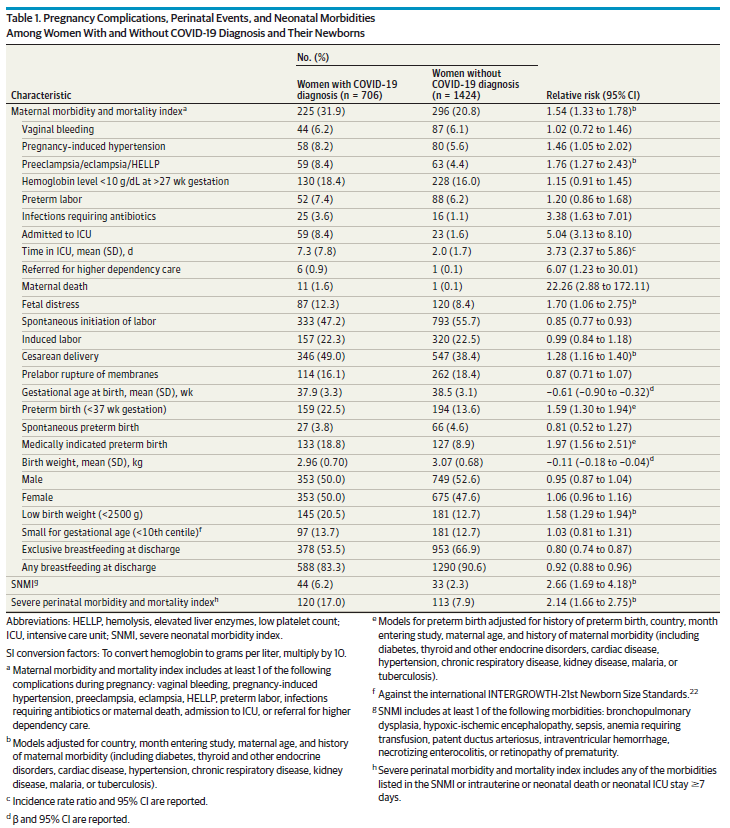

Meanwhile, we have the first large and controlled study that monitored pregnancy outcomes for those who were infected with COVID-19 versus uninfected pregnant people. The table below is BUSY. To avoid getting overwhelmed, I recommend looking at the characteristic column and then the last column (relative risk). What this measures is how much more or less likely the outcome was for pregnant people who were infected with COVID-19 compared to those who were uninfected. If the number is at or near 1, it’s about the same risk in both populations. If the number is less than 1, then it was less likely to occur in the infected population. If the number is above 1, it is more likely to happen in the infected population.

Things that were more common among those who were infected while pregnant include maternal death (22x more likely), referral for higher dependency (high risk) care (6x), admission to the ICU (5x), infections requiring antibiotics (3.4x), and were about twice as likely to have a medically necessary preterm birth.

Taking these two studies together about the risk of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and the safety of the vaccines for these individuals and their newborns, you can understand why the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have been recommending vaccination for pregnancy and those trying to become pregnant for months now.

Infections following vaccination

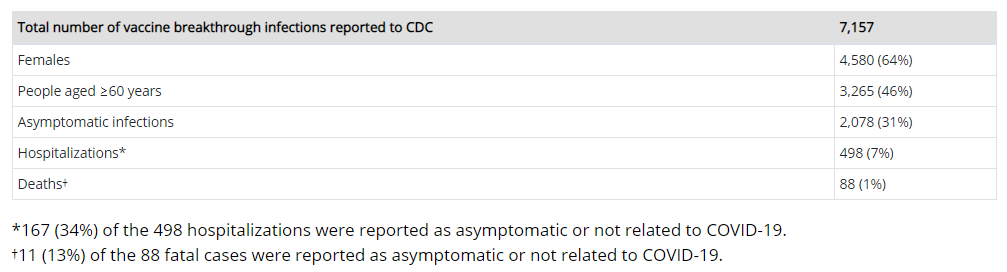

The vaccines are very, very good at preventing infection. But they’re not 100% effective in this. Infection following vaccination is very rare, but as more people are vaccinated and taking additional risks afterwards, we should expect to hear more about breakthrough cases. Let’s go over what we know. You can follow this information from CDC to see how the situation evolves over time in the future.

As of 20Apr, there have been over 87 million people fully vaccinated in the US. As of that same date, there have been 7157 breakthrough cases. That’s an 0.008% infection rate. Of the breakthrough cases, there have been 2078 that were asymptomatic, or 0.002% of vaccinated people. There have been 498 hospitalizations among fully vaccinated people, although 34% of those were due to reasons other than COVID-19. In any case, that amounts to 0.0006% of fully vaccinated people. For deaths, there were 88 cases where a person tested positive for COVID-19 at or near the time of death but 13% of them died due to unrelated causes (i.e. car accidents, etc). This amounts to 0.0001% of fully vaccinated people.

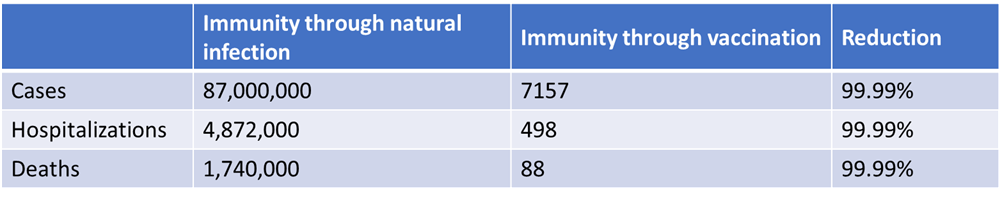

The goal, of course, is to get to herd immunity - a threshold where enough people have achieved immunity from COVID-19 that there is so little community transmission that even those who aren’t immune are protected from disease. We can get there one of two ways - through natural infection (brute force) or vaccination. Let’s compare the numbers knowing what we do now about a population of 87 million people who have been fully vaccinated. Now, of course, this is not a perfect comparison since we may be undercounting breakthrough cases, but hospitalizations and deaths are more reliable and show the same reduction. We want to get 87 million people to immunity. The first column is through natural infection, so 87 million cases. The second column is through vaccination. So based on the CDC data, that’s 7157 cases. Based on what we know about hospitalization (5.6% of cases through natural infection) and death rates (2% of natural infections) so far we can estimate how many hospitalizations and deaths would occur if we deliberately infected 87 million people: 4.87 million hospital admissions and 1.74 million deaths in the US.

I think it’s pretty clear from these numbers that the safest way to achieve population-level herd immunity is through vaccination. Communities can choose to go the brute force path (natural infection), but it will mean a lot of pain, suffering and death to get there. I suppose it comes down to how much a community values its people. If you view people as expendable, then perhaps it doesn’t matter to you if a lot of people die, as long as it’s not you. If you recognize that each person has inherent value and contributes to the success of your community, then losing anyone you don’t have to lose is a tragedy. I would tend to argue that we should care about other people, but a surprising number of people don’t share that opinion. Learning that has been one of my greatest disappointments in this pandemic.

Transmission following vaccination

By now, you’ve probably learned that you get COVID-19 by inhaling viral particles that were exhaled by another person. The amount of viral particles that a person can exhale varies based a combination of how vigorously they’re breathing (i.e. shouting, singing, or breathing heavily expels more particles) and the amount of virus they carry in their body (known as viral load). We know that vaccines really strongly reduce the risk of infection (see section above), and I think we can appreciate that you’re probably less likely to transmit virus if you’re not infected in the first place. That’s because the virus hasn’t had a chance to replicate enough inside of your body to be detected by PCR testing. If its undetectable in the body, it’s likely too low of a viral load to contribute to transmission.

But I think the thing many of us worry about is that we could be asymptomatically infected after vaccination and inadvertently pass that infection on to others who aren’t protected. It’s a lot of the same anxiety that existed prior to the advent of the vaccines. None of us want to put people we care about at risk. Because asymptomatic cases are less likely to be detected in the real world, it’s important to assess this risk in studies where people are routinely tested for the presence of virus or antibody response to virus, regardless of symptoms.

For Johnson and Johnson, they looked at this in their clinical trial and you can read a full explanation that I previously wrote here. Briefly, they looked at antibodies produced against the full SARS-CoV-2 virus (causes COVID-19 disease) before and after day 29 post-vaccination among those who were vaccinated and those who received placebo. They found that after 29 days, there was a 74% reduction in asymptomatic infections among vaccinated people compared to placebo recipients. So you’re a lot less likely to have symptomatic infection after vaccination, in general. But you’re also 74% less likely to be unknowingly infected too. We’re compounding these risk reductions here so the possibility of transmission becomes very, very small.

We also have some data for other vaccines, where the researchers were actively testing for the presence of virus using PCR, regardless of symptoms. This is better than looking at self-reported cases or population incidence data where asymptomatic cases would be missed. The graph below comes from a study that monitored SARS-CoV-2 PCR test positivity among healthcare workers in Texas who were either unvaccinated, partially vaccinated or fully vaccinated with either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines. We can see that the risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of symptoms, was 98.1% less when you were fully vaccinated than if you were not vaccinated at all. This is one study and among those I’ve seen that look for the presence of virus regardless of symptoms (only available for Pfizer or Moderna so far), the vaccine effectiveness ranges from 86-92%.

PCR is a pretty sensitive test, able to detect low quantities of virus. Cases can be missed, of course, if the sample collection from the patient is inadequate. But if a person tests negative by PCR, it means there’s little to no viral load there to begin with and these people are likely not infected. In addition, with low or no viral load, the chances of transmitting virus to others are exceedingly small.

The graph above is also a really good visual illustration for us to see how important it is to get that second dose of the vaccine if you’re doing the 2-dose series.

A study recently came out from the UK that looks at transmission to household contacts of healthcare workers who have been vaccinated compared to households where the healthcare worker was not vaccinated. This is an interesting study, but not quite as good as the others because they were passively collecting data on testing - just whoever happened to seek a test who lived at the same address as an identified healthcare workers. They were not actively or routinely testing people regardless of symptoms. So it isn’t a straightforward apples to apples comparison with the other studies we’ve talked about so far. In addition, in the UK both the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines were available, but the national priority was getting first doses on board, extending the spacing between first and second doses. So this study doesn’t look at transmission following second doses, just what happens if one dose is on board. With that understanding, they found that a single dose of vaccine reduced household transmission by 40-50% when the vaccinated healthcare worker was 21 days past their first dose. This number is good but not terribly impressive. So I’ll remind you of a few things that could play a role: (1) they were only looking at the effectiveness of one dose of vaccine when both manufacturers recommended 2. (2) These household contact cases weren’t investigated for other possible exposures. With cases being what they were in the community, it’s possible that household contacts got disease elsewhere. (3) The timing of testing didn’t exclude the possibility that the household contact was the person who brought disease into the home, going on to infect the vaccinated healthcare worker, rather than the other way around.

I think the thing that matters here is that while getting sick following vaccination is rare, it is more common than we would like right now because case rates in the community are still high. Increased vaccinations and low community transmission are the one-two punch and their effects combine. The more people we vaccinate, the lower community transmission rates will be. We can speed that process along, of course, by limiting transmission wherever we can including by wearing masks, social distancing, good air ventilation, etc. The vaccines reduce (a)symptomatic infections by 74-98%, but clearly the risk of infection following vaccination is not zero. We reduce that gap in effectiveness with low community transmission rates. Vaccinations can do a lot of the work for us. But we have to do some of the work too. Eventually we get to a point that community transmission is low enough that few if any cases happen among vaccinated people. Cases may still happen among unvaccinated people, but to a much smaller degree than we are observing now.

Georgia

Testing

Today there was a net increase of 20,214 newly reported PCR tests (5% positive) and 7,412 antigen tests (6% positive). Antigen testing identified 30% of today’s newly reported cases.

Cases

There were 1011 newly reported PCR cases and 433 antigen cases today for a combined total of 1444. State wide case rate is nearly equivalent to the post-winter surge base (+3.4%) and the case rate is highest in the Atlanta Suburb counties and lowest in rural counties.

Hospitalizations

Today there was a net increase of 130 newly reported confirmed hospital admissions and 22 admissions to the ICU. These are typical numbers for Georgia lately. There are two hospital regions using >90% of their ICU beds, in the red zone (regions A and N). All hospital regions are in the yellow (n= 3, regions A, F, N) or green zone for COVID-19 patient census. Naturally, I’d prefer that all of these numbers be zero, but Georgia is in an okay place right now.

Deaths

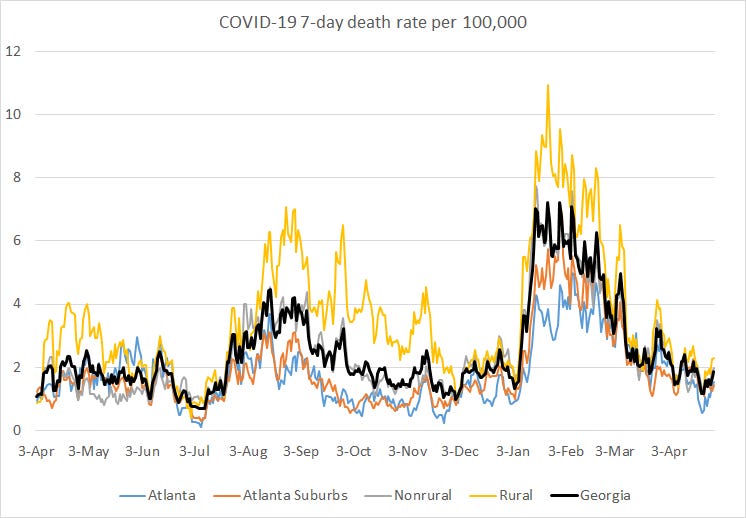

There was a net increase of 48 newly reported confirmed COVID-19 deaths and 12 probable ones today, for a combined total of 60 deaths. The state death rate is in this cycle of boom and bust that largely coincides with weekend lags in reporting. But the net effect is this continued downward trajectory.

So things are flat, and dare I say calm, for the time being in Georgia. While I’m out for surgery tomorrow, I hope that the situation remains that way. Keep going on autopilot or get better (please!). When I was teaching undergraduates, I had this uncanny ability to predict incoming hurricanes based on when I had scheduled exams. For one course, every exam had to be rescheduled because of school closures related to hurricanes or other mishaps. So when I scheduled this surgery for tomorrow, I chuckled to myself that tomorrow will probably be a big COVID-19 news day. Because that’s how fate seems to work. Hang in there, I’ll be back hopefully on Sunday or Monday with a week in review. I’m sure my husband will mention to the surgeon tomorrow that a lot of people depend on me (in addition to my husband and children), to encourage him to be careful. No pressure, Doc!

Assuming that major news doesn’t happen first, an interview I did on vaccination rates is supposed to be on the CBS Evening News with Norah O’Donnell this evening. The story was bumped yesterday, hopefully it airs tonight.

References

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2102153

https://khub.net/documents/135939561/390853656/Impact+of+vaccination+on+household+transmission+of+SARS-COV-2+in+England.pdf/35bf4bb1-6ade-d3eb-a39e-9c9b25a8122a?t=1619601878136

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2104983?query=recirc_mostViewed_railB_article

https://www.acog.org/covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-and-pregnancy-conversation-guide-for-clinicians

Georgia COVID-19 Updates is a free newsletter that depends on reader support. If you wish to subscribe please click the link below. There are free and paid options available.

My Ph.D. is in Medical Microbiology and Immunology. I've worked at places like Creighton University, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and Mercer University School of Medicine. All thoughts are my professional opinion and should not be considered medical advice.

Thank you for doing all you do every week to keep us all informed! Keeping you in our thoughts as you head into surgery and hoping for speedy and easy recovery.