Week in Review, 28Jun - 02Jul2021

COVID-19 Updates

This week, the Georgia DPH put out a press release that they would no longer update the COVID-19 data dashboard on weekends or holidays. On the one hand, this is probably long overdue. I’m not sure how much of their updating is automated and/or how much requires a person to manage it over the weekends. But public health workers need the break and the weekend reporting is usually light anyway. We aren’t missing anything that couldn’t wait. Whoever typically oversees these updates, I hope you are able to get the rest you deserve.

On the other hand, there’s a piece of this that feels like the beginning of a slippery slope that leads to completely eliminating COVID-19 data reporting from the state. This week the state of Nebraska announced they were no longer maintaining or updating their COVID-19 data dashboard. The state’s citizens will only get updates when the state feels like providing them. By ending the state of emergency, the state is closing a lot of its testing sites also. It is unclear if they will continue to report cases at a county level to the CDC. Meanwhile, only 47.8% of Nebraska’s population is fully vaccinated against the disease. Just down the road, in Missouri (where 39.2% of the population is fully vaccinated), we’re starting to see the danger of low vaccination rates and surging case rates with hospitals once again reaching their peak COVID-19 patient census in local hospitals. It’s naive to think that a similar situation couldn’t happen for Nebraska. The difference now is that citizens won’t know what’s coming. Imagine a hurricane headed for your state, but the weather forecast was not being provided to you so you could prepare.

The vaccines are wonderful, but not perfect. They are just one mitigation strategy as we think about how to keep individuals and communities safe. Given that none of our risk mitigation strategies are perfect, they are represented as pieces of swiss cheese in the infographic below. The best way to protect ourselves and our communities is to layer multiple pieces of cheese (multiple imperfect interventions) together. Ideally, this is a combination of personal and shared responsibilities. As case rates in your local community climb, you need to add more strategies. As case rates lower, you can lift some (but not all) of the strategies. Disease control is not a finish line. It’s something we have to work hard to maintain.

There’s a lot of confusion lately about whether to wear masks anymore, even if fully vaccinated, because there’s conflicting recommendations between CDC and WHO. WHO is now recommending even fully vaccinated people wear masks in crowded settings, knowing that vaccination rates are low throughout many parts of the world (including parts of the US) and delta variant is wreaking havoc. CDC still recommends masks, regardless of vaccination status, for homeless shelters, childcare centers and prisons. The vaccines are just one of several strategies we have, and the best one we have, but it is still best for us to layer these things together.

Ideally, we need to combine 2-3 strategies at all times. If your area has low case rates and is in the blue or yellow category for disease transmission rates, that counts as one of them. If you’re also fully vaccinated, you’re in good shape. But if you can’t be vaccinated or you have chosen not to do so, then you need to pick different strategies you’re going to follow to protect yourselves and your community. If case rates in your area begin to surge, you need to add more strategies. We need to adapt to changing conditions. Maybe your state or community has decided masks are no longer necessary. Be prepared that this policy may change when delta (or other variants) cause surges in your area. And you don’t need a government mandate to take steps to protect yourself or your family anyway. Remember, these mitigation strategies are not for forever, we need to flex to changing conditions. But the more we pull together to layer the pieces of cheese, the less opportunity we give the virus to move to others, to mutate into more challenging variants, and to harm the people around us.

A warning in southwest Missouri

We’re starting to see the impact of the delta variant in areas with low vaccination rates, and ground zero for this is southwest Missouri. I did an analysis of Missouri in late May for a presentation (see left map below) and what we can see is that for the most part, areas with greater vaccination rates are along the I-70 corridor between Kansas City and St. Louis, through the mid-section of the state. Like Georgia, Missouri is a state with significant rural-urban divide. Fast forward to present time (right map) and we can see that large sections of the state are still below 25% vaccinated and none of the counties have reached 70%. For a lot of the counties, they didn’t really advance from one color tier to the next over the course of a month. Even the green counties are somewhere between 25 - 35% vaccinated, which is quite low.

Now look at what’s happening with case rates and test positivity, from the most recent HHS State Profile Report.

Hospitals in southwest Missouri are turning away COVID-19 patients, diverting them to less-stressed hospitals in Kansas City and St. Louis. Either city is a long drive from southwest Missouri. The Governor of Missouri has requested “public health strike teams” from the CDC to bulk up testing, contact tracing and vaccinations in southwest Missouri. Meanwhile, the delta variant is just getting started in Missouri, making up 55% of the variants of concern in the state. For Georgia, delta makes up just 6% of the variants of concern and 36.7% of the state’s population is fully vaccinated. Missouri has a higher vaccination rate (39.2%) than Georgia. If delta gets going in Georgia, we could anticipate a similar surge as what Missouri is experiencing. I dislike the DPH’s maps for displaying vaccination rates because they use a color ramp that makes it look like Georgia counties are doing really well. It makes it hard to see where the vulnerabilities are. If we consult the vaccination rates by county according to Georgia DPH, using the same scale as I previously showed for Missouri, then we see that there are some real areas of vulnerability. This is especially the case for hospital region M in southeast Georgia. None of the counties have reached 70%.

And this is a good reminder of a few things. Without data, we are blind to what is happening. So let’s hope that Nebraska reverses course and none of the other states consider shutting down their data reporting to the public. Second, the outbreaks of the future are going to be at a county or regional level within a state. So it will be really important that states give authority to local leaders (i.e. mayors, county commissioners, etc) to respond to local outbreaks with mask ordinances, social distancing, changes for the dining industry, etc. Remember, no one enjoys these strategies. They are there to protect lives. If local leaders can issue a boil water advisory due to contaminated drinking water, local leaders should be able to respond to local COVID-19 outbreaks.

As a reminder, it’s not too late to get vaccinated. Please make an effort to do so at your earliest convenience. I was able to locate my son’s second vaccine dose while we were traveling on vacation thanks to the vaccines.gov website. It was a really helpful tool.

Georgia

There are some things to keep an eye on for Georgia. First is testing. Testing output has been decreasing steadily since the peak in late January. For a long time, we’ve been able to get away with that as test positivity matched that rate of decline and dropped under 5% for several weeks. But we’re starting to see that trend reverse. For three weeks in a row, the test positivity rate has started to swing back upward. It’s under 5% for now, but how long will that hold? Like case rates, low test positivity is not a finish line. It is something we have to work to maintain. Something to remember is that this “week” is actually 5 days, as we all adjust to DPH’s new policy of not reporting on weekends. From now on, my “weeks” will consist of Monday - Friday data collection. So there is a big drop in testing output (blue line) this week, but part of that is probably explained by missing two days’ worth of data.

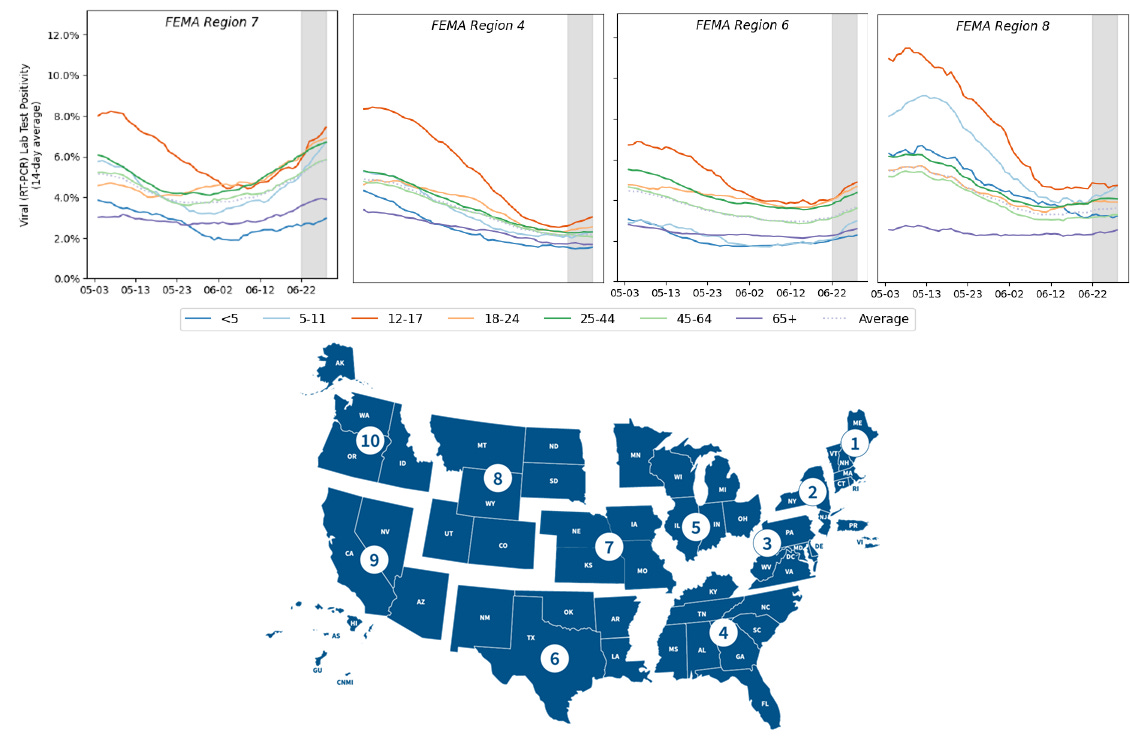

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) divides the nation into regions. The South is in region 4. Missouri is found in region 7. The graphs below show how test positivity is changing over time (14 day average) by age group, from the HHS Community Profile Reports. In region 7, we can see that test positivity is rising and well above 5% for all age groups, but less so for those under 5 years old and those 65+. That means that we are missing cases, more so with each passing day. If we look at region 4 (the South), most age groups are pretty flat. But there is a clear increase happening for those 12-17. Georgia needs to be more vigilant in testing adolescents and teens. Test positivity is also increasing for multiple age groups in region 6. If we look at region 8 (Mountain West and upper plains states), things are flat for most age groups, but rising among 5-11 year olds. A common thing among all of these graphs is that test positivity is highest in 12-17 year olds. These kids are eligible for vaccines, but may not be getting them. Their test positivity is highest and/or rising, meaning we are missing cases most in this age group.

What’s interesting is that if we look at the counties with test positivity above 5% in Georgia, they are largely rural and they are in the areas with low vaccination rates. So if delta is going to make a play in Georgia, the areas with low vaccination rates and insufficient testing will likely be among the areas will be problematic. We will be able to see that there’s a problem, but might not have the testing infrastructure in place to accurately measure or control disease spread through testing contact tracing. As a reminder, rural counties are the ones hit hardest so far when it comes to deaths in Georgia.

If we zoom in a bit closer to the 7-day case rate per 100,000 for county types since June 1, we can see that case rate for rural Georgia is climbing. In fact, it’s climbing everywhere except in the Atlanta counties of Fulton and DeKalb. Fulton and DeKalb have some of the highest vaccination rates in the state. This may help to explain why their case rate has stayed low. But we should keep an eye on the rest of the state, where things are climbing.

We also may want to keep an eye on what’s happening in hospital region I, some of the reddest parts of the state for recent case rate and now showing an increase in patient census at the hospital for COVID-19.

So where are we? For the most part, things seem flat. But there are a handful of things that are starting to tick upward for Georgia that we should keep a careful watch on and consider adding an additional disease prevention strategy. Even though this week only had 5 days’ of cases reported compared to 7 last week, they have nearly the same case total. So this may have probably been a larger than usual week.

As always, please make good decisions that are considerate of others. The lives we lose to COVID-19 are preventable and there are steps we can and should take to save them by preventing exposure in the first place.

References

https://dph.georgia.gov/press-releases/2021-06-29/covid-19-daily-status-report-and-covid-vaccine-dashboard-updates

https://virologydownunder.com/the-swiss-cheese-infographic-that-went-viral/

https://www.kmov.com/news/hospital-in-hard-hit-springfield-turns-away-covid-patients/article_e3e0e734-d921-11eb-b614-af2d0b7cf050.html

https://healthdata.gov/Community/COVID-19-State-Profile-Report-Missouri/cq69-gktb

https://www.kansascity.com/news/coronavirus/article252503893.html

https://nextstrain.org/groups/spheres/ncov/missouri?c=emerging_lineage&m=div&r=location

Georgia COVID-19 Updates is a free newsletter that depends on reader support. If you wish to subscribe please click the link below. There are free and paid options available.

My Ph.D. is in Medical Microbiology and Immunology. I've worked at places like Creighton University, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and Mercer University School of Medicine. All thoughts are my professional opinion and should not be considered medical advice.